Proposed regulations have an uphill battle to speed PG&E’s switch from mobile diesel to cleaner, more cost-effective alternatives by 2021.

California regulators and utilities want to build microgrids for communities most at threat from the state’s increasingly deadly wildfires, and the widespread public safety power shutoff (PSPS) grid outages meant to prevent them. But despite policies to fund and enable these microgrids, California is still far from finding effective ways to get them in place for next year’s fire season.

Even Pacific Gas & Electric, the utility most affected by wildfires and fire-prevention blackouts, is struggling to find solutions to replace the hundreds of megawatts’ worth of mobile diesel generators it’s secured to back up Northern California communities facing power outages. This week, the California Public Utilities Commission issued a proposed decision to boost action on these fronts, including earmarking up to $350 million for utility “clean substation microgrid” proposals in the 2021-2022 timeframe.

The CPUC’s proposed decision, set for a vote in January, also takes steps toward enabling community- and third-party-operated microgrids, as required under 2018 state law SB 1339. Those include expanding the potential for multicustomer microgrids and ordering the state’s investor-owned utilities to create microgrid tariffs or standards for sharing costs and benefits of the services microgrids can provide.

But the CPUC’s past two years of efforts to rush microgrid development haven’t had the desired effect. PG&E’s plan for multiple substation-based microgrids powered by natural-gas generators faltered in the face of community opposition and pushback from clean-energy advocates, while the state’s other investor-owned utilities were unable to find cost-effective microgrid projects.

The CPUC and PG&E have been working with microgrid vendors and communities to break through this impasse. An August CPUC workshop provided sample microgrid solutions from vendors including Tesla, Sunrun, Bloom Energy, FuelCell Energy and Enchanted Rock, as well as presentations from two Northern California community-choice aggregators building renewable energy microgrids.

Challenges with clean, cost-effective substation-based microgrids

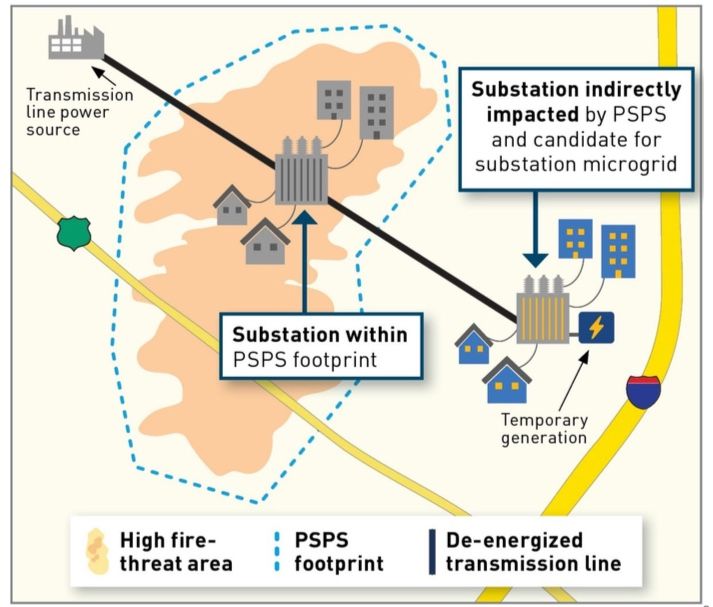

Quinn Nakayama, PG&E’s director of integrated grid planning and innovation, highlighted these complications during Greentech Media’s Grid Edge Innovation Summit 2020 event last week. Nakayama’s discussion spanned from “substation microgrids” concept — backing up substations that lie outside high fire-threat areas but will be deprived of power by transmission lines that must be shut down during wildfire-prevention outage events — to smaller distributed microgrids.

(Image credit: PG&E)

One of the key challenges with clean energy-powered microgrids, Nakayama said, is that they would have to rely on batteries that can only cost-effectively store about four hours of power and massive amounts of solar PV to charge them. That would be too expensive for backup power that has to last for up to three days in a row.

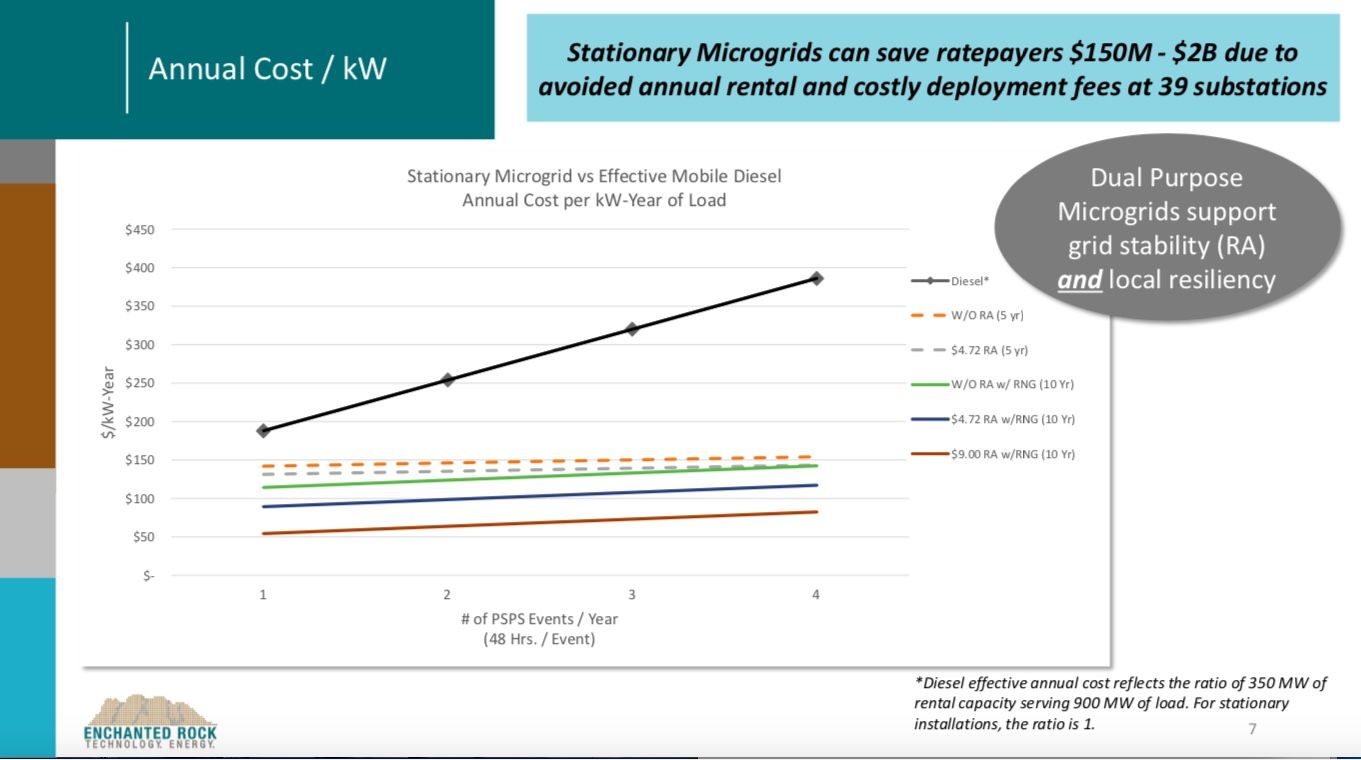

Natural gas generators would be a more effective solution, he said. But permanent generators for blackouts that only happen a few days per year are a hard sell, compared to mobile units that can be moved from blackout spot to blackout spot. Any long-term installation must earn money when the grid is still running to pencil out economically, which in California’s case calls for providing resource adequacy (RA) services to the wholesale markets run by grid operator CAISO.

Unfortunately, the areas that PG&E has identified as microgrid targets lack transmission capacity needed for “deliverability” to CAISO’s network, he said. Finding ways around this constraint without being forced to invest in expensive transmission upgrades will be vital to making substation microgrids cover their costs over time.

“It’s cost-effective because you’re not bringing trucks to move them between locations; you’re not doing these temporary installs,” he said. “And it’s a safer installation because mobile solutions are filled with extra steps, and if you miss one, you can have a safety issue.”

To unlock RA revenue, CAISO could decide that offsetting load on its transmission system could avoid deliverability limits, he said. And Enchanted Rock’s generators could help support solar and battery growth, and eventually use zero-carbon fuels like renewable natural gas, to meet the state’s long-range carbon-reduction goals, he added

(Image credit: Enchanted Rock)

Building microgrid business cases from the individual customer and up

But to Tim Hade, COO of Scale Microgrid Solutions, the approach of starting at the substation is wrong-headed. “At some point, they’re going to have to pivot and realize this is going to have to be a distributed solution,” he said in a November interview.

This might not be as attractive to utilities, since substation-based microgrids are a capital expense recoverable from ratepayers, whereas distributed solutions lack that clear payback. Even so, utilities will “have to make significant upgrades to a distribution system to make it happen, so there’s a good chunk of rate base for PG&E,” he noted.

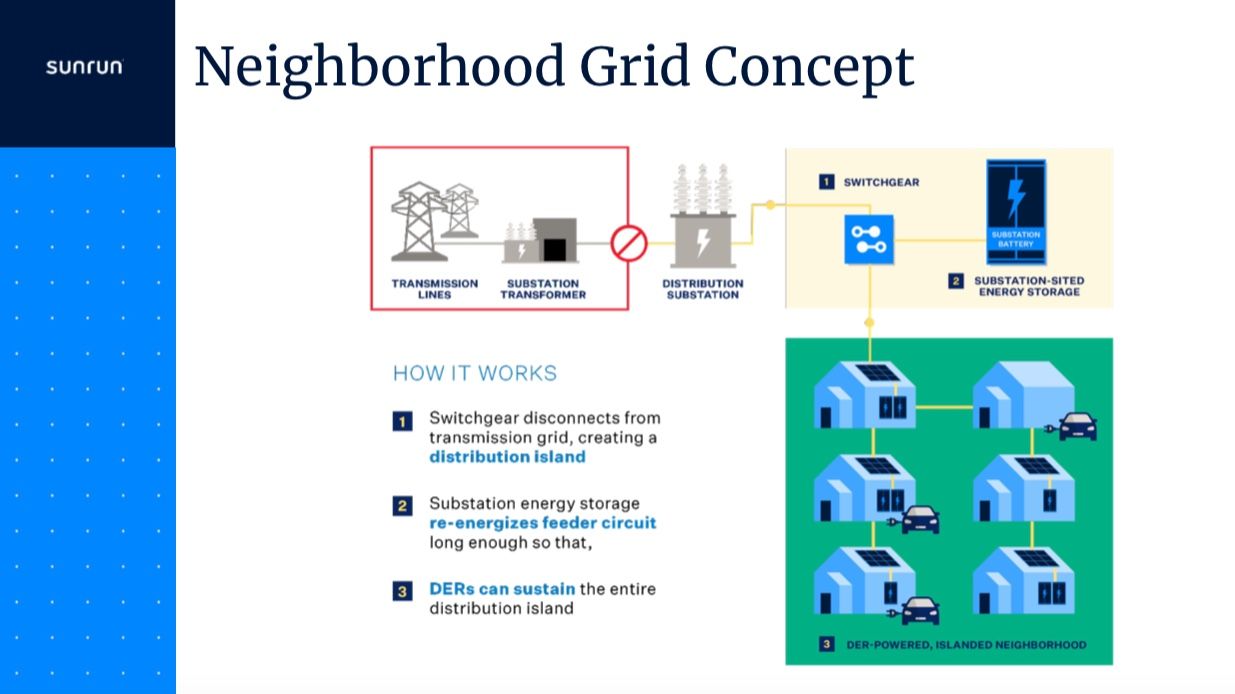

Leading U.S. residential solar installer Sunrun, for example, has laid out a “permanent, renewable, distributed” microgrid concept, using multiple solar-storage systems backed up with centralized batteries and fuel cells behind a disconnected section of grid, that it says could cost less than the equivalent diesel backup.

(Image credit: Sunrun)

This aligns with California’s imperatives to boost clean power adoption, Walker Wright, Sunrun’s VP of policy, said in a November interview. It can also tap existing revenue streams from solar net metering and funding sources like the state’s Self-Generation incentive Program for behind-the-meter batteries.

Distributed microgrids face significant technical challenges, PG&E’s Nakayama pointed out. Inverter-based power sources would have to be finely controlled to provide the constant, stable power that distribution grids need.

“Otherwise, if there’s not enough energy, the whole grid will collapse,” he said. Even with fine-grained control, inverter-based generation resources can play havoc with the fault current sensors and line reclosers that keep grids safe from outages or overloads, he said.

Distributed microgrids may also run afoul of regulations barring the sharing of power between customers, Walker said. The CPUC’s proposed decision takes an initial stab at this problem by proposing to allow multiple government buildings next to critical facilities to share microgrid services.

But other microgrid stakeholders are asking the CPUC to expand these cross-customer sharing opportunities. “We’re not the only stakeholder to say that the state has to take a close look at the over-the-fence rules,” Wright said.

Bloom Energy has proposed using its fuel cells at substations and at points along the distribution system. Running them 24 hours a day could defer transmission upgrade costs and deliver power more efficiently than far-off generators, Chris Ball, head of product marketing, said in a November interview.

Bloom also has more than 100 microgrids running today, including an installation at Sacramento’s Sleep Train Arena set up this summer to support emergency COVID-19 patient treatment, and a Santa Rosa, Calif. manufacturing facility that rode through a five-day wildfire-prevention outage in 2019, he said.

Microgrid regulations and revenue: A work in progress

Finding ways to reward these customer-owned microgrids for their possible service during wildfire-prevention outages will require “a technology-neutral tariff for customer-owned microgrids,” Ball said.

PG&E’s Community Microgrid Enablement Program, approved by the CPUC earlier this year, includes creating a form of tariff to share costs between customers and the utility, and the CPUC’s new proposed decision tasks all three of the state’s investor-owned utilities to propose similar tariffs in the next year.

CPUC’s proposal for creating microgrids for multiple municipal buildings could be a first step, said Isaac Maze-Rothstein, a Wood Mackenzie analyst specializing in microgrids. “Being able to have that in 30 communities across California to prove out how this works could be significant.”

A new proposal to require California’s investor-owned utilities to create microgrid incentive programs could also help, he said. The CPUC intends to direct $200 million toward these incentives, with no more than $15 million available to any single project.

But “the holy grail for microgrid project developers is reliable, consistent revenue,” he said. Microgrid tariffs will be vital for that purpose, both to clarify what microgrids must pay utilities in the form of departing load and standby charges, and to set the revenue they can earn, not only for the electricity they supply the grid but also for the resiliency they provide.